Evidence-Based Reading Instruction (EBRI) for Adult Learners: The Why and How

by Dr. Marija Privitera and Trista Houghton Mason

With the recent shifts in language acquisition instruction across all educational fields, the phrase “science of reading” gets thrown around a lot. But what does it really mean, and specifically, does it have an impact on adult learners? The short answer is YES!, it does. The Science of Reading (SoR) can be defined as “a vast, unfinished, continuously growing, and evolving interdisciplinary body of scientifically based research about reading and issues related to reading and writing” (Lawson, 2022, unpaged). Although most of the discussions in the field are focused on evidence-based instruction in PK–12 institutions, there is much to be said about the importance of developing a well-rounded language acquisition program in adult classrooms. Much like in the other learning environments, adult language programs must provide learners with explicit reading instruction that supports two pillars—the phonics component and the comprehension track. The assumption that we must choose between the two is simply not correct.

So, What Should Reading Instruction for Adult Learners Look Like?

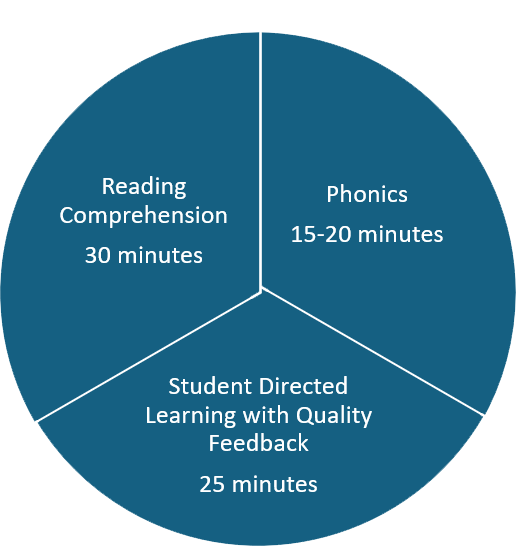

The phonics piece of any class should be approximately 15–20 minutes. During this time, the students should have access to high-quality lessons focused on phonemic awareness and decoding. Phonemic awareness includes activities such as identifying beginning, middle, and ending sounds; blending sounds to make words, word segmentation, and sound manipulation. On the other hand, decoding involves the manipulation of letter and sound correspondence; such as deleting, adding, or blending sounds to make new words. Having a structured curriculum helps, but even without it, plenty of free resources are available to educators. The current research recommends that meaning-based and phonics-based approaches must be deployed for successful language acquisition. It also shows that explicit teachings of phonics and phonological memory can enhance adult learners’ language acquisition within these parameters in as little as 14 weeks of meaningful, structured decoding instruction.

For the second part of the reading class, the instruction should focus on the reading comprehension strategies. Providing explicit instruction in reading comprehension strategies may lead to increased reading comprehension achievement. For adult learners, it is important that they understand the purpose of reading the text, be able to preview it, and engage in activating prior knowledge and connections to the topic. One of the connections between phonemic awareness and comprehension instruction can be developed by using vocabulary words from the text preselected during the phonics part of the class, although these two parts of the class do not have to be on the same topic. Keep in mind, however, that precursors to reading comprehension are decoding and fluency. Choose text levels that correspond to the student’s level of English language proficiency, their decoding/reading level, background knowledge, interest, and goal for reading the text. Students’ intrinsic and extrinsic motivation and understanding of a task are especially important for adult learners.

What do Adult Learners Need?

Looking at andragogy, the primary adult learning theory, adult learners tend to do better when their learning is self-directed and quality feedback is provided. In terms of reading instruction, this can be achieved by allowing students to freely choose their learning paths such as flipped classroom, peer collaboration, or mini-stations. Additionally, providing timely feedback validates students’ efforts and guides the next steps in self-directed learning. Quality and factual feedback should be concise and actionable, providing the adult learner with clear next steps. Reading resources are often geared towards the K–12 student and it is important to know your students’ background knowledge and interests to connect adults to appropriate texts. The Virginia Adult Learning Resource Center (VALRC) website can be accessed for professional development opportunities and resources connected to this topic.

References

Baker, S. K., Beattie, T., Nelson, N. J., & Turtura, J. (2018). How we learn to read: The critical role of phonological awareness. U.S. Department of Education, Office of Elementary and Secondary Education, Office of Special Education Programs, National Center on Improving Literacy. https://improvingliteracy.org/code-assets/briefs/how-we-learn-to-read-the-critical-role-of-phonological-awareness.pdf

Lawson, B., (2022). What is the science of reading? The Reading League. https://www.thereadingleague.org/what-is-the-science-of-reading/

ReadWA. (2022, April 30). The science of reading 2 0 [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BVBlywaNI9o

Scarborough, H. S. (2001). Connecting early language and literacy to later reading (dis)abilities: Evidence, theory, and practice. In S.

Neuman & D. Dickinson (Eds.), Handbook for research in early literacy, (pp. 97–110). Guilford Press.

Additional Resources

Phonemic Inventories and Cultural and Linguistic Information Across Languages

Perspectives on Language and Literacy: The Role of Phonology and Language in Learning to Read

When Home and School Language Differ

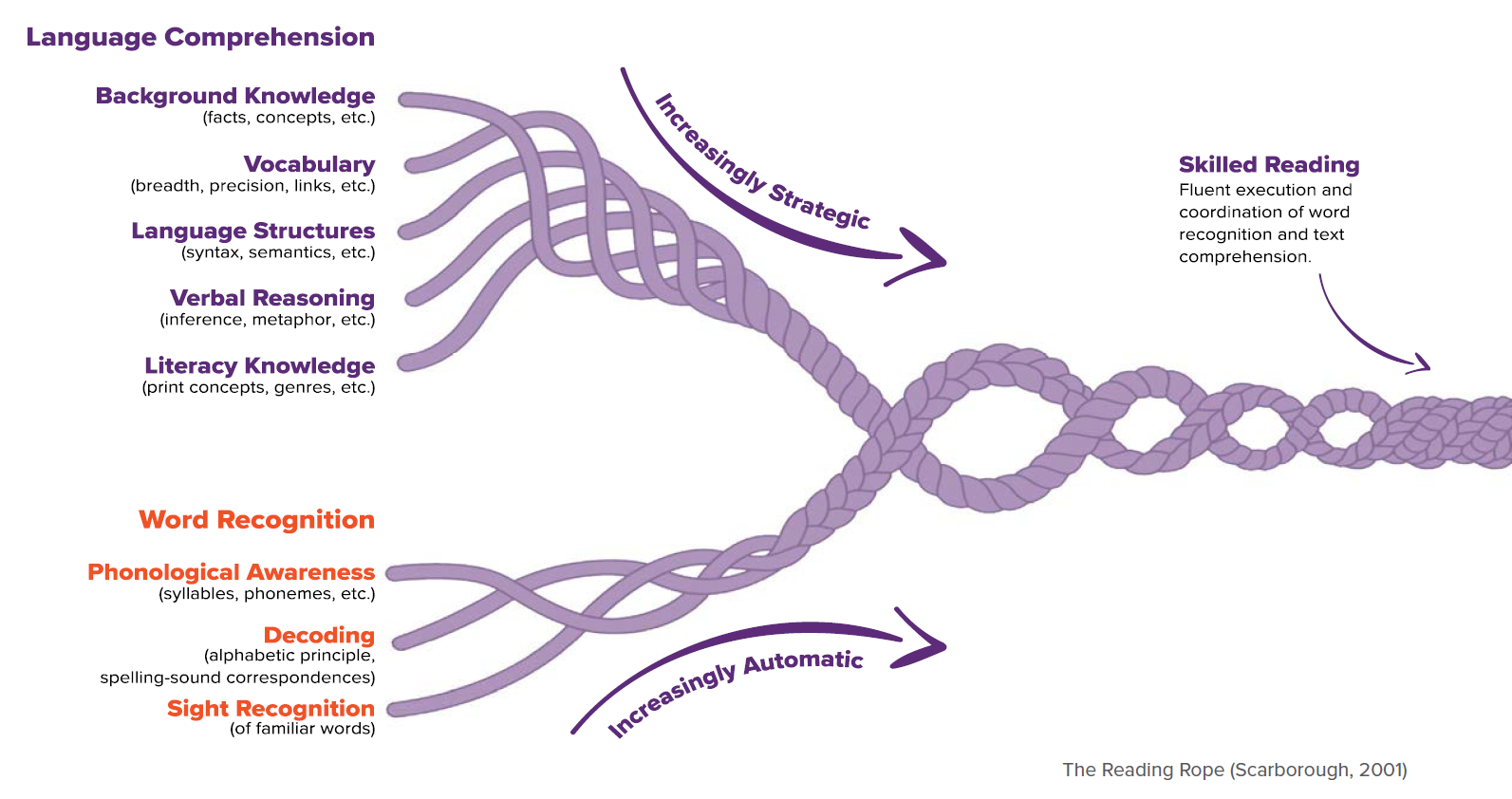

The Scarborough’s Reading Rope (2001) provides a more in-depth understanding of the subcomponents within word recognition (WR) and language comprehension (LC). It is a visual metaphor for the development of skills over time (represented by the strands of the rope) that lead to skilled reading.

The Reading League. (2022). Science of reading: Defining guide. https://www.thereadingleague.org/what-is-the- science-of-reading/

The Reading League. (2022). Science of reading: Defining guide. https://www.thereadingleague.org/what-is-the- science-of-reading/

Dr. Marija Privitera is an experienced and passionate educator with more than 20 years of experience. She holds a doctoral degree in educational leadership from Liberty University and has worked as a health and physical education teacher, Reading Specialist, Instructional Coach, Coordinator of Federal Sustainability Programs, and a doctoral studies applied research expert. Dr. Privitera is a VDOE Adult Education and Literacy Committee board member and VDOE English Language (EL) Regional Teacher Trainer. As a language learner and immigrant herself, Dr. Privitera focuses her work on the language acquisition of multilingual learners through the application of the Science of Reading (SoR).

Dr. Marija Privitera is an experienced and passionate educator with more than 20 years of experience. She holds a doctoral degree in educational leadership from Liberty University and has worked as a health and physical education teacher, Reading Specialist, Instructional Coach, Coordinator of Federal Sustainability Programs, and a doctoral studies applied research expert. Dr. Privitera is a VDOE Adult Education and Literacy Committee board member and VDOE English Language (EL) Regional Teacher Trainer. As a language learner and immigrant herself, Dr. Privitera focuses her work on the language acquisition of multilingual learners through the application of the Science of Reading (SoR).

Trista Houghton Mason, M.A., M.Ed., has more than 20 years of experience in the education field. A dynamic leader, she has instructional experience that spans Pre-K through postsecondary and has held school-based and site-based leadership roles in divisions across the state of Virginia. Currently the Supervisor, Sustainability of Federal Programs for Prince William County Schools Central Office; she is dedicated to providing meaningful and equitable opportunities for all students, with an emphasis on multilingual learners. Ms. Mason has also been an adjunct professor since 2016 with Northern Virginia Community College in the Early Childhood Department.

Trista Houghton Mason, M.A., M.Ed., has more than 20 years of experience in the education field. A dynamic leader, she has instructional experience that spans Pre-K through postsecondary and has held school-based and site-based leadership roles in divisions across the state of Virginia. Currently the Supervisor, Sustainability of Federal Programs for Prince William County Schools Central Office; she is dedicated to providing meaningful and equitable opportunities for all students, with an emphasis on multilingual learners. Ms. Mason has also been an adjunct professor since 2016 with Northern Virginia Community College in the Early Childhood Department.