Professional Learning Communities in Action: Initial Responses & Next Steps

by Hillary Major

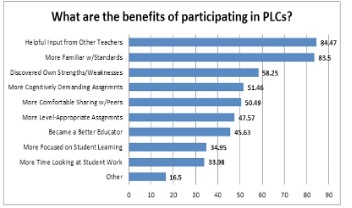

In early spring 2017, we surveyed adult educators around the state who had participated in professional learning communities (PLCs) focused on standards-based instruction. Following a summer 2016 facilitator training on using a CCR Standards-in-Action protocol to analyze and revise assignments, more than 60 new PLCs were launched across the state. More than 40 of these met at least four times, beginning to set a collaborative routine for participants. 125 PLC members responded to our survey. When asked about the benefits of PLCs, more than 80% said they received helpful input from other teachers and became more familiar with standards. Nearly 60% reported that they discovered more about their own strengths and weaknesses as educators.

When asked about the benefits of PLCs in an open-ended question, many responses focused on the benefits of collaboration. “The opportunity to just TALK together about specific things was invaluable. Got great ideas for all sorts of things,” wrote one respondent. Another reported that they had formed a “much closer relationship w/some teachers [they] rarely saw otherwise. We are now friends. Great feedback. Great ideas. Very supportive people.”

Some respondents focused on including standards and the CCRS key shifts in their lesson planning: “increased repertoire of lesson resources,” “commitment to continue to match standards to all lesson assignments,” “thinking about rigor of assignments and not worrying about students having to push deeper to do the work.” Responses showed PLC participants responding to different aspects of the Standards-in-Action protocol. A teacher wrote, “I include rubrics at more stages for myself and the students’ use”; the protocol prompts PLC members to discuss the “scoring guidelines” for assignments. The protocol also focuses on how well an assignment’s tasks are aligned to standards and whether students’ work shows that they understood the assignment and are demonstrating the assessed skills. A PLC participant wrote, “[I am] reconsidering how I give assignments – clarity of instruction has improved. Also reflecting more on teaching of writing and how to correct writing and engage students in process writing.”

The opportunity to just TALK together about specific things was invaluable.

While the large majority of responses were positive, not all were. For example, one educator wrote, “There was nothing of benefit gained from participating in the PLC. Adult is very different from [a] regular classroom ….” Because the Standards-in- Action student work protocol asks educators to bring in several examples of student work responding to a single assignment, it can be a challenge for instructional settings that rely heavily on individual, independent work or one-to-one tutoring. This can be an opportunity to focus on how instructional delivery may need to be adapted to achieve full implementation of standards-based instruction; the Standards-in-Action Observation Tools, for example, place a high priority on student collaboration, discussion, and engagement with tasks that go beyond textbook worksheets. PLC group members can help strategize ways to find meaningful opportunities for small group work in multilevel classes, creatively use multimedia to increase student engagement or connect with other learners, or suggest ways a tutor can vary the types of interaction within a one-to-one session. The protocol asks teachers to share an honest example of their current practice and then participate with peers in making revisions; teachers with different levels of experience may demonstrate different strengths and weaknesses, but all have room to grow through reflection and peer feedback. PLCs give an opportunity for programs to harness the professional wisdom of their instructional staff, using an evidence-based structure and resources to guide the discussion.

The challenges Virginia educators reported in implementing PLCs were overwhelmingly related to scheduling and logistics: 34% of survey respondents selected “logistics (e.g., scheduling)” as a challenge, which was the highest response to that question. Additionally, 33% of respondents reported “other” challenges, nearly all of which (like budgeting for professional development hours or driving distances to PLC meetings) also focused on logistics. Only 5% of respondents reported “low attendance” as a challenge, indicating that programs and educators made their commitment to PLCs a priority.

The protocol asks teachers to share an honest example of their current practice and then particpiate with peers in making revisions.

While more than half of responding PLC participants reported developing more cognitively demanding assignments (51%) and becoming more comfortable sharing with peers (50%), somewhat fewer reported craft-ing more level-appropriate assignments (48%) or that they became a better educator (46%). Despite the focus of the protocol, only about a third reported that they became more focused on student learning (35%) or spent more time looking at student work (34%). The reasons for this are uncertain: quite possibly, teachers who invested in PLC participation already considered themselves to be strong educators, committed to their learners and to continuous improvement of their own practice. Perhaps some respondents similarly felt they already prioritized looking at student responses and making formative assessments of student learning. Another possibility is that many participants found becoming familiar with the standards to have a bigger impact because CCR standards were relatively new and because the first task of the protocol involves assessing the demands of an assignment and matching it to standards, while the process of looking at student work comes later in the session. Continuing to offer PLC sessions after participants have become more familiar with CCR standards might lead more participants to focus on the formative assessment aspects of the protocol.

Did PLC participants continue to meet into the 2017-2018 program year? We don’t have comprehensive statewide data for this year, although a few regions have continued to report on their PLC meetings. Some regions that have continued PLCs have taken the opportunity to reach a larger number of teachers across their programs, in some cases using teachers who participated in 2016-2017 PLCs as facilitators for new PLC groups.1 The benefits reported by PLC participants offer a compelling argument for making PLCs a central part of professional development for all adult educators. PLCs using the Standards-in-Action student work protocol exemplify the features of “high-quality professional development” (see page 14).

The benefits reported by PLC participants offer a compelling argument for making PLCs a central part of professional development for all adult educators.

For regions that have already offered some PLCs using the Standards-in-Action protocol, options for wider rollout include:

-

forming additional PLC groups to reach more teachers (perhaps having experienced PLC members serve as facilitators);

-

continuing PLC meetings using the Standards-in-Action protocol beyond the minimum four (or one per participant) meeting sessions,

-

giving instructors additional opportunities to workshop their own assignments and give constructive feedback to peers,

-

allowing participants to focus on a different subject area (e.g., math or English language arts/ literacy), or

-

choosing a specific sub-focus for the activities workshopped by the PLC (e.g., having all participants bring in activities that incorporate workforce preparation, include a rubric, target learners at a skill level that often struggles to make gains);

-

-

offering a PLC that does not use the Standards-in-Action protocol but instead takes an inquiry approach to a local regional or programmatic challenge. This option is most appropriate for educators who are already familiar with state instructional standards; staff developing and facilitating such PLCs should be mindful of incorporating the features of high-quality professional development, including an evidence basis, and providing structure that encourages effective time management and participation from all PLC members. The Resource Center is happy to share models and discuss facilitation considerations.

I am always happy to hear PLC success stories from around the state, stories of teachers learning from each other and supporting each other in pushing their instruction to the next level. If you are considering how to draw on the power of PLCs for your region or program, I (and my Resource Center colleagues) would love to talk!

Hillary Major is Instructional Standards and Communications Specialist at the Virginia Adult Learning Resource Center.

1 PLC facilitators should be familiar with the Standards-in-Action student work protocol (either from attending a train-the-trainer or through PLC experience). They should be be comfortable leading by example, knowledgeable about standards (able to guide discussion to ensure key standards or shifts are not overlooked), and willing to speak up to enforce time management and constructive feedback guidelines (or effectively delegate those roles). If you need to train additional PLC facilitators, please contact Hillary Major at VALRC for more information.