What is the Benefits Cliff?

by Dr. Jeff Price

“A small pay raise or extra work hours can actually make the family worse off financially because the increase in earnings is not enough to replace the loss of benefits.”

Means-tested programs are anti-poverty programs meant to serve as both a safety net to severe deprivation and assistance for low-income households to develop their capacity for financial self-sufficiency. Federal means-tested programs generally provide benefits in cash (TANF, Earned Income Tax Credit, child tax credit) or in-kind (SNAP, WIC, Child Care Assistance, Medicaid). Most of these anti-poverty programs were created as part of the “Great Society” domestic agenda of President Lyndon Johnson (1964). They are designed to respond when economic conditions change for the worse and more families need assistance. Eligibility is based solely on need, unlike social security and unemployment, which require prior contributions. Anyone below the benchmark set for each program is eligible.

While the benchmark for each program is different, eligibility is determined by comparing household financial resources (earned and unearned income, expenses on food, housing, utilities, health care) to the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) to evaluate or “test” the extent to which the family has the “means” to provide for itself. For example, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) is limited to those with incomes below 100% FPL. Eligibility for the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP) is limited to those below 130% FPL. Medicaid is limited to those below 185% FPL. Earning any amount above these limits results in the immediate loss of program benefits. These sharp eligibility cutoffs create a series of “benefit cliffs” in which earning an extra dollar results in losing benefits often worth several hundred dollars.

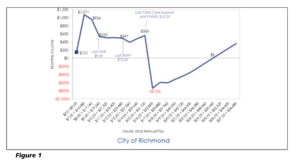

Because eligibility for means-tested assistance programs is set low relative to the actual cost of living, there is a wide gap between program income limits and the income needed to be financially self-sufficient. For example, a single mother in the city of Richmond with two young children in day care needs to earn over $67,000 per year ($32 per hour at 40 hours/week) to be self-sufficient. Yet she will lose eligibility for all means-tested programs if her income exceeds $30,500 per year ($15.25 per hour) (Figure 1).

A small pay raise or extra work hours can actually make the family worse off financially because the increase in earnings is not enough to replace the loss of benefits. In particular, eligibility for FAMIS, child care assistance, and housing subsidies are the last benefits to be lost but have the greatest impact on family finances. Households may not earn enough to replace these lost benefits and become self-sufficient until they reach two to three times the poverty level. As many researchers have shown, the actual cost of housing, food, transportation, child care, etc., in each locality is much higher than the FPL.

While children and older adults make up a large portion (about 60%) of the population receiving benefits, these programs are primarily focused on the working poor and often include a requirement that the head of the household comply with certain work requirements (e.g. minimum of 20 hours employment per week, or engage in training, education, or job search).

The potential sudden net loss in family resources can create a disincentive for enrollees to work or earn more or to participate in education and training programs that could put them on a path toward higher long-term earnings and eventual self-sufficiency. A study in Colorado examined the behavior of working mothers receiving the Colorado Child Care Assistance Program (CCCAP), a child care subsidy for low-income working parents, and found that families whose earnings were near the upper-limit of the program’s eligibility guidelines turned down extra work hours and raises in order to preserve their subsidy. It also found that increased exposure to the cliff effect produces an increasingly negative impact on workforce participation (Goldfarb, 2019).

The disincentives are compounded by uncertainty about whether investment in training and education will pay off. Accepting a job now with existing skills may provide immediate steady income, but limited opportunities for future advancement and higher earnings. When considering other career options, both short-term and long-term impact on household finances should be considered Job counselors and career coaches are trained to assess each person’s situation and explain the path required to become qualified for certain types of jobs and to pursue a career in a particular occupation. They will develop a plan that includes the specific courses and tests that may be required. Ideally, they will also identify the support services needed to provide a stable financial environment while the individual pursues their career goal.

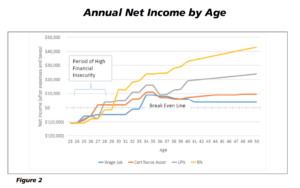

Hence, each career pathway has a net income pathway that accounts for changes in earnings, household expenses, and tax rates over time. Investing in more education generally entails a period of negative net income and financial insecurity (while in school or training), followed by higher earnings that accumulate rapidly compared to career options that do not require as much education. The second figure illustrates net income pathways for a 23 year old considering a basic wage job, a certified nurse assistant, a licensed nurse practitioner, and a registered nurse. Net income changes over time as expenses and earning change. The cost of raising children, for example, is high when they are young but drops off as they become adults. Also, the age at which the decision is made impacts the expected return on investment in a career pathway. The decision to pursue an occupation requiring a two or three year program of study at age 37 will not have the same long-term return on investment that it would at age 23 because there are not as many productive years left for the individual.

Counselors, educators, and social workers should develop a good understanding of what the benefit cliff is, what the trigger points are, and how it impacts decision making for low-income working individuals.

Every adult has had to make this decision at some point in their life. What do I want to do with my life? How do I get from where I am today to where I want to be? What are the costs and tradeoffs I will face in the short term and what will the payoff be in the long-run? The decision to pursue a career that requires greater education and training but the potential for much higher earnings is difficult enough for individuals and families with adequate resources. For those at the lower end of the income scale with children, debt, and possibly other barriers, it is often a bridge too far. The benefit cliff cuts critical support just when it is really needed. Food, transportation, shelter, child care, and health insurance are essential to adults who will experience reduced earnings while they are trying to earn a credential for a better job.

What can be done? First, counselors, educators, and social workers should develop a good understanding of what the benefit cliff is, what the trigger points are, and how it impacts decision making for low-income working individuals. In addition to explaining what the training, testing, or academic requirements are and the range of income that may be expected for each career option, counselors should also assess and explain what the short- and long-term financial costs and tradeoffs are as well. The Federal Reserve of Atlanta has developed a tool called CLIFF (Career Ladder Identifier and Financial Forecaster) to help counselors, social workers, and policy makers evaluate career pathways and the financial implications.

In addition, some states are experimenting with new approaches to reduce the benefit cliff effect. For example, Virginia now extends childcare subsidies for 12 months after eligibility is lost due to hitting the income limit. In addition, benefits now taper off rather than ending abruptly (childcare copayment amounts increase gradually with higher income). Colorado is implementing similar changes to their programs as well.

Lastly, randomized controlled studies are needed to isolate and quantify the impact the benefit cliff has on labor force participation, and the social cost of continuing to provide public assistance under the current policy structure versus alternative policies that would reduce or eliminate the benefit cliff and replace it with more effective incentives for low-income working individuals to become financially self-sufficient.

Reference:

Goldfarb, K. (2019). Pushed over the edge with nowhere to land: Summarizing key qualitative findings concerning the benefit cliff effect in Connecticut. Connecticut Association for Human Services.

Dr. Jeff Price is the Director of the Office of Research and Planning, and the Chief Data Officer at the Virginia Department of Social Services where he leads data warehousing operations, research and business intelligence reporting, performance management, and agency-wide data governance operations. His office supports state policy makers, program managers, and local agency directors. Jeff earned his master’s degree in anthropology and a Ph.D. in agricultural and applied economics from the University of Georgia. He has been a Virginia state employee for 18 years.

Contact: [email protected], 804-726-7617