Designing Instruction in Ways That Can Reach All Learners: Applying the Principles of Universal Design for Learning

by 2019 AE&L Conference Presenter Dr. Frances G. Smith

Think back for a moment to a recent learning experience that left you with a positive impression. Was the instructor engaging? Did they hook your interests from their first words? Did you feel like the information was personalized to something you wanted to learn? How about the ways that the information was presented—were the materials provided in multiple formats? Did the presenter use various modes of sharing their information? Finally, as a learner, did you have a fair opportunity to demonstrate your understanding? Were there optional ways for you to show what you knew?

These are the questions every adult educator should be considering as they design instruction for learners. Adult learners want to know why they are learning and to be actively involved in the process. Equally, they are more motivated by approaches that match their interests, background, and diversity (Brian, Kreuler, & Brownson, 2009). Applying the research-based framework of universal design for learning (UDL) ensures that educators are designing instruction that recognizes this variability and diversity in learners (CAST, 2018a).

What is Universal Design for Learning?

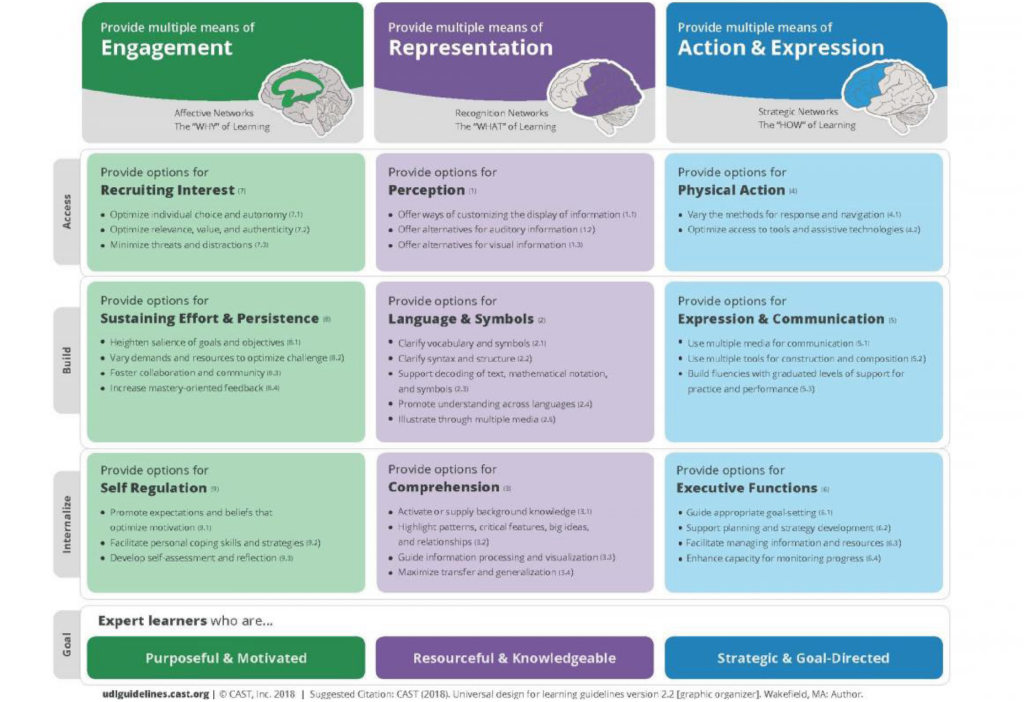

Universal design for learning (UDL) is an educational framework that places an emphasis on offering optional ways to represent information, engages the learner in the lesson or instruction, and allows the learner to demonstrate their knowledge. Three core principles underscore this practice.

-

Provide multiple means for engagement, offering multiple options that support the why of learning with a focus on recruiting interest, encouraging persistence, and developing self-regulation.

-

Provide multiple means for the representation of information, offering multiple options that support the what of learning that focus on perception, language and symbols, and comprehension.

-

Provide multiple means for action and expression, offering multiple options that support the how of learning and provide options for physical action, expression, and areas for executive function.

In 2008, UDL was officially defined in the Higher Education Opportunity Act of 2008 (20 U.S.C. § 1003(24)). These three principles and the affordances they provide were acknowledged, including for those with disabilities or who are English Language Learners (ELLs). This definition continues to be included in federal policies such as those related to K-12 education, instructional technology, and career and technical education.

Why is UDL Important for Adult Educators?

Through a UDL lens, adult educators can design their instruction in ways that support a wide diversity of learners. Research from the learning sciences has continued to support how differing contexts, learner preferences, developmental stages, and backgrounds can impact how the brain learns (CAST, 2018a). For example, an adult learner in their early twenties may have greater capacity in their working memory than someone in their six-ties. An individual entering a classroom from a different country may also have very different cultural and background experiences than learners who grew up in the U.S. system. Watch this video of Dr. Todd Rose discussing how important variability is when we plan for the learners in our classroom.

Students come to the classroom with a variety of needs, skills, talents, interests, and experiences. For many adult learners, typical curricula are littered with barriers and roadblocks, while offering little support. UDL turns this scenario around by encouraging the design of flexible, supportive curricula that are responsive to individual student variability. Through a UDL lens, adult educators can consider multiple ways to offer options in how they represent the content, how students demonstrate their understandings, and how students are motivated to learn the material.

The UDL approach also focuses on explicitly teaching students the skills they will need to become life-long “expert learners.” UDL improves adult educational outcomes for ALL students by ensuring meaningful access to the curriculum within an inclusive learning environment. The UDL framework includes 3 core principles, 9 guidelines, and 31 checkpoints that can be considered when designing a curriculum or classroom (CAST, 2018b). These are detailed across the UDL Guidelines and provide links to suggested approaches, online examples, and evidence-based research. Consider the visual.

The UDL framework provides adult educators with a lens for instructional planning that offers guidelines and checkpoints across these three areas. For example, recognizing the value of choice and relevance in a classroom is critical in recruiting student interest. Designing goals that are clearly stated, personalized, and relevant to assignments helps students see the value in the materials they are learning. Re-thinking how materials are presented to students is critical when considering their ability to perceive and comprehend information. Rather than a page of instructions, information might be provided as a graphic organizer that highlights key points through shapes and relationships. Offering a digital space for course materials can also provide content in a format that students can more easily magnify, highlight, or speak aloud.

Advances in technology have provided many opportunities for adult educators to embrace as they design their courses. Some of these are free or low cost. For example, the TextHelp® software tool Browse Aloud can be incorporated into a website, blog, or online program and provide “speech-aloud” support, translation, and synchronized highlighting. In addition to offering a range of embedded supports, this allows a student who may prefer audio over print to listen to a document online or easily select a language they understand. This also helps them to learn more about the availability of these tools and how they may be of use to them in the future. In fact, Spanish-speaking individuals seeking to explore future careers and related information through the national O*NET database can now access this tool in Spanish.

Where Can I Explore More Resources?

The application of UDL across an array of resources and settings can be found in a number of online locations. Below is just a sampling of some that may be of use to adult educators.

- CAST

- CAST Free Learning Tools

- Learning Designed

- UDL on Campus

References

Bryan, R. L., Kreuter, M. W., & Brownson, R. C. (2009). Integrating adult learning principles into training for public health practice. Health Promotion Practice, 10(4), 557563. https://doi. org/10.1177/1524839907308117

CAST (2018a). UDL and the learning brain. Wake-field, MA: Author. Retrieved from http://www. cast.org/our-work/publications/2018/udl-learn-ing-brain-neuroscience.html

CAST (2018b). Universal Design for Learning Guidelines version 2.2. Retrieved from http://udlguidelines.cast.org

Dr. Frances G. Smith, Educator/ Consultant of Recognizing Differences, LLC, is an innovative educator and implementer of the practices of universal design(s) for learning. She has over 30+ years in instructional and assistive technology—providing direct service to students with disabilities, staff development training to educators, and serving on statewide advisory boards. Dr. Smith has presented on array of topics as a national and international speaker including the importance of universal design for learning.

VALRC offers resources and support to help you build UDL into your instruction or program! Take a look at the Professional Learning page on our website.

Need some tools so your students have alternative ways to present their assignments? Check out Tech Tools.

“Through the UDL lens, adult educators can consider multiple ways to offer options in how they represent the content, how students demonstrate their understandings, and how students are motivated to learn the material.”

Consider this scenario:

Maria has her sights focused on developing a business. In her country, she had a completed degree in a related field and had managed a food business. However, when she came to the U.S., she found that her lack of language skills created a significant barrier to her ability to advance. She has signed up for adult education classes to strengthen these skills and to obtain her GED© credential so that she can pursue additional coursework. However, as Maria enters the classroom, she finds that most of the instruction is provided through lecture and relies on a great deal of printed materials.

Through a UDL lens, the instructor might consider blending her lecture with digital presentations that offer more interactivity. Using multiple means of representing the instruction through audio, a YouTube video, or website could expand opportunities to support Maria’s understanding. The increasing array of embedded technology supports in many of today’s media often include “speech-aloud” functions that can read the text online in English or another language. Video recording that complements content can often provide another means to demonstrate a process that might be quite abstract when presented just through a lecture.

In addition, instead of a large group or traditional classroom lecture, the adult instructor might consider clustering students into smaller groups. This might encourage small group interaction, discussion, and opportunities to personalize topics for individuals. Students might also work in pairs to problem-solve tasks and benefit from each other’s perspectives. These adjustments can expand upon the multiple ways to engage students with the content and, in this case, the classroom environment, as well as foster an important sense of community.

Finally, the adult educator might consider offering multiple ways for the students to demonstrate their knowledge. This, too, may be helpful for other classes that Maria may encounter as she explores future courses in business. Thus, rather than a single test to measure proficiency, perhaps the instructor might allow this student to share a portfolio of her completed work and a collection of various artifacts. If computers are used in the classroom, this could become a digital portfolio and a student might excel in demonstrating their understanding through optional means by sharing a well-crafted PowerPoint, a Prezi, an infographic, or perhaps a video. For students who may have more significant needs, offering opportunities with digital options expands the reach for those who may rely on the use of assistive technologies or require audio, closed-captioning, or synchronized highlighting to provide the information they are exploring and understanding in different formats.