Creating Space for Civics in Adult Multilingual Classes

by Melanie Siteki

A few words come to mind when I think of civics education: participation, inclusion, and of course, community. Images come to mind too, of people and all the places where we gather.

At the heart of these spaces and the concrete words even beginning-learners use to identify them, lies shared values. “School” represents our hopes for our children, ability to work, and joy of discovery; and “Park” brings to mind the environment we share with trees, animals and our neighbors. By including civics in our lessons, we can highlight these values and explore the messy process of decision-making.

At the heart of these spaces and the concrete words even beginning-learners use to identify them, lies shared values. “School” represents our hopes for our children, ability to work, and joy of discovery; and “Park” brings to mind the environment we share with trees, animals and our neighbors. By including civics in our lessons, we can highlight these values and explore the messy process of decision-making.

I’ve used the following strategies and resources across levels and adapted them to a variety of contexts to integrate civics into multilingual classes.

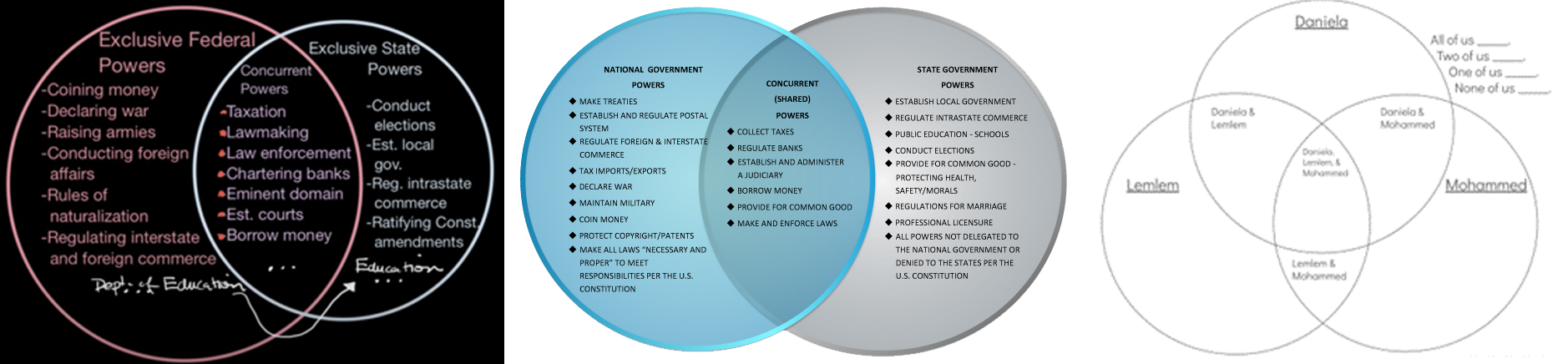

VENN Diagrams (and other graphic organizers)

Venn diagrams, consisting of overlapping circles, can be used to build classroom community and teach history and government content. From day one, they help learners discover what values, experiences, hopes, needs, goals, or interests they share.

They are also useful for introducing, brainstorming, and otherwise engaging with complex civics content such as rights and responsibilities or state and federal powers of the U.S. government—basically any topic that involves comparing, contrasting, or sorting.

Sources: Khan Academy, Civic Education VA

Language Frames

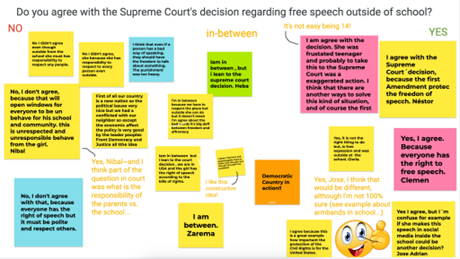

When preparing for a class with potentially difficult topics, sentence starters are a useful tool across levels. Learners will practice agreeing and disagreeing with respect, asking questions, and changing the subject. The class will learn to initiate speaking and keep conversations going. They can be introduced when making decisions together about class rules and topics, practiced during conversations or role-plays using cards or strips of paper, and displayed so learners can refer to them when they might come in handy.

|

“I have a different point of view…” “Have you ever thought about…?” “I care about you, but I disagree because…” “What if…” “What do you think…” |

“When you say _____, I feel…” “I would like…” “Have you considered…?” “At first I thought…but then I learned…” |

|---|

Source: Colorín Colorado

Community Engagement, Problem Solving, and Decision Making

Group and partner interviews about neighborhoods, legal issues (e.g., police and immigration), work, health, and transportation are an effective way to practice problem solving in English and share experiences. After interviewing a volunteer student in front of the class about a problem, learners can reflect on their own experiences and interview each other in small groups, provide feedback, and discuss possible solutions. At this point, each group can prepare a skit about one of the experiences or situations and/or write about their own or a classmate’s story. The instructor and class can use a bulletin board for sharing community resources.

Voting on class rules and topics, sharing opinions, and conducting surveys are effective activities to make decisions together as a class and learn about the process of civic engagement in the United States (Civics Class Slides).

Bring the wider community to the classroom by planning in-person or virtual field trips to local libraries, museums, or community events. These experiences provide a shared moment that can be leveraged to facilitate language learning opportunities.

Guest speakers to our program have included County and School Board members, and community partners such as public health, community outreach, and the local One-Stop career center.

Focusing on Civics

Choose civics texts that allow engagement with difficult questions, conflict resolution, helpful advice and information, examples of community and courage, and stories and resources that represent all people, including those who are marginalized. Teachers can remind learners of their right to an interpreter in health care, legal, and other contexts. Everyone has the right to ask for help to bridge the gap between English ability and access to resources and participation in civic life.

“Webquest” type activities provide access to online materials, while jigsaw and information gap activities can help learners engage complex texts with civics content in communicative ways.

The language in history and government texts is often complex, formal, and—with primary sources such as the Constitution and Bill of Rights—also antiquated. We can “translate” these into everyday language (see Slides).

At a very basic level, we need to provide space to support community and civics engagement. From a social-emotional learning perspective, we can also model patience and respect. Having a few extra moments to process empowers learners. Learners will feel the agency that comes with real communication. Building language skills and civic awareness will give learners the confidence to engage in their larger community space.

I will close with the philosophy that I explicitly share with my classes: don’t wait to participate in your community—you are already an essential part of it. Language proficiency exists on a spectrum, but being a part of the community does not. Civics transcends language and no one should be excluded from rights and responsibilities because of their English proficiency.

Resources

Best Practices in Civics Education: A Case Study

LINCS: Integrated English Literacy and Civics Education Resources

Google Slides from Melanie’s ACCESS Class

TSTM Skillblox Resource Library

Melanie Siteki has taught a variety of levels with the Arlington Education and Employment Program (REEP) since 2001, including REEP’s Advanced Culture, Civics, and English Studies (ACCESS) curriculum. She has a bachelor’s degree in anthropology and modern languages and a master’s degree in language, culture, and humanities education. She loves creating language learning materials and is now enjoying being back in the classroom with high-beginning learners after three years teaching online.

Melanie Siteki has taught a variety of levels with the Arlington Education and Employment Program (REEP) since 2001, including REEP’s Advanced Culture, Civics, and English Studies (ACCESS) curriculum. She has a bachelor’s degree in anthropology and modern languages and a master’s degree in language, culture, and humanities education. She loves creating language learning materials and is now enjoying being back in the classroom with high-beginning learners after three years teaching online.