Life of a DSS Client: Their Struggles & Family Concerns

by Vicki Krusie

“Efforts to engage in education or training can be derailed by persistent struggle.”

A recent ALICE (Asset Limited, Income Constrained, Employed) report from the United Way provides alarming statistics for Virginia. Based on data from 2018, it states that while the economy showed some improvement (prior to the COVID-19 pandemic), 10% of Virginia households remained below the federal poverty level and another 29% earned above the poverty level but not enough to afford household basic necessities—the ALICE population. Programs offered through the Virginia Department of Social Services (VDSS) provide assistance for both basic and crisis needs for those who meet the eligibility criteria. Others remain unserved. Services offered through multiple workforce programs offer connection to education, employment, and training. Many services are free or based on income. Not all are eligible or willing to engage.

The complexity of the issue requires ongoing analysis and discussion across multiple systems in search of evidence-based practices, but that is not the focus of this article. Instead, we are here to explore the actual daily challenges for those behind the politics and the numbers. So, take a walk with me through one real story of an unemployed individual below the poverty threshold who received assistance from the Department of Social Services (DSS) in York County.

“Laura” is a single parent of two school age children. She does not have a high school diploma and has worked a variety of low-wage jobs. She grew up in a household with an alcoholic mother, and her childhood experience was tumultuous. According to the CDC-Kaiser Permanente Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study, she is at risk for lifelong health issues and emotional well- being in adulthood. At entry into the VIEW program (VA Initiative for Education and Work), Laura was slow to form trusting relationships and frequently felt overwhelmed with her life circumstances. She was prone to outbursts of anger when confronted with stressful situations. This hampered her ability to successfully resolve conflict and remain employed. There were instances of involvement with law enforcement, but no felony convictions. Every morning she woke up with the threat of possible eviction and the subsequent loss of custody of her children to the non- custodial father. Frequent telephone calls from school concerning her child’s behavioral and academic problems cost her one job. Mandatory counseling sessions required by the court threatened another. At program entry, Laura could not afford her own transportation to work and requested assistance from the local DSS VIEW staff, which was provided. Inconsistent after-school child care, lack of a high school diploma, outstanding fines, and sporadic work history further hindered her efforts to find stable employment. She stated she was too overwhelmed to pursue GED® classes, although she insisted this was a goal for herself.

Over the next several months, Laura began her journey to improved financial stability. She cautiously engaged with agency staff and reluctantly began the Customer Service Academy, a local DSS grant- funded initiative which provided a certificate from Thomas Nelson Community College. She began working with her DSS case manager and a Life Coach to help her set goals and tackle obstacles. She completed a short- term certification and began employment. She received her tax return and purchased a vehicle. And with assistance, she resolved one outstanding housing judgement and began payment on another. During this time, there were ups and downs, frequent phone calls to discuss setbacks and problem solve, and countless small victories such as “I wanted to cuss them out but I did not lose my cool.” With each accomplishment, her confidence grew—with each setback, she struggled to navigate yet another roadblock.

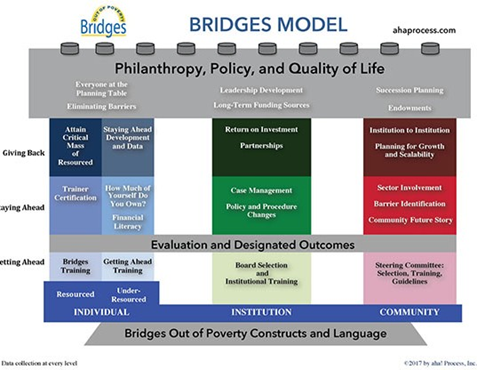

Laura’s case is not unique. The “Bridges out of Poverty” model defines poverty as “the extent to which an individual does without resources”. Poverty is not limited to just lacking finances, but to a variety of resources including the emotional resources that enable us to deal effectively with negative situations. Individuals can get caught in the “tyranny of the moment” as they regularly confront the reoccurring need to pay rent, maintain utilities, put food on the table, pay for a car repair, obtain child care, get to work on time and the list goes on. Lack of viable support systems can result in poor choices further complicating the situation. Efforts to engage in education or training can be derailed by this persistent struggle. Realistically, outcomes for our families are not measured by finite words such as success or failure. Instead, progress is incremental, with some achieving a higher degree of success than others.

Although her case is now closed due to income (just above the poverty threshold), Laura continues to call her previous case manager whenever the need occurs. Recently, the case manager called to report another crisis. Laura was frustrated, defensive, and angry. Efforts to problem solve were hindered by emotion. The end result? Alternatives were discussed, and we wait to hear how her story unfolds.

Vicki Krusie is a Self-Sufficiency Supervisor for the York-Poquoson Department of Social Services. She is responsible for the VIEW (VA Initiative for Education and Work) and Child Care programs. In addition, she supervises both the Service Intake and Community Resource operations of the agency.